|

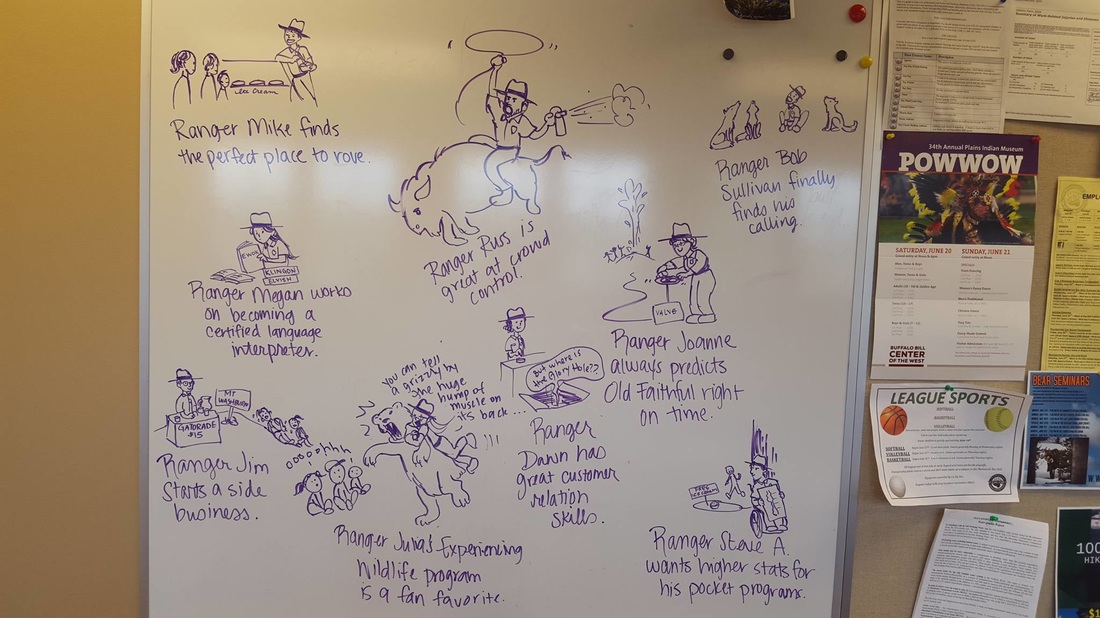

I can’t believe how fast the summer is going. In just another few weeks, our interns will leave, kids will go back to school, and visitation in Great Smoky Mountains National Park will scale back dramatically, at least until leaf season in October. It’s been a great season full of bug-hunting in the river with Junior Rangers, telling stories on the Mountain Farm, and shaking our fists at the elk standing defiantly in the garden eating acorn squash. But I’ve been keeping a list. I started this list last year in Yellowstone. It’s hard not to. So much of a front-line park ranger’s job is visitor services that we quickly figure out how to get to the bottom of what a visitor is looking for in their park experience. I’m currently reading The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker, where the golem can sense other people’s wants and desires. I can’t think of another superpower I would rather have when a visitor comes to the desk, tells their kids to hush, and asks me, “What is there to do here?” I’ve compiled a few suggestions for folks planning to travel—anywhere, really, but especially to your national parks. It’s not exhaustive. I’m sure other rangers at different parks could chime in with a thousand more things. But these are some basics to keep in mind when planning your trip. 1. DO PLAN YOUR TRIP I think there is a very romantic idea in people’s heads about hopping in the car with a full tank of gas and half a pack of cigarettes and embarking on a spur-of-the-moment Great American Road Trip. I doubt this method worked well even in the Halcyon Days of Route 66, but it works even less well now, despite what Instagram will have you believe. National parks, at least at high season, are crowded places. Campgrounds fill up. Entrance lines are long. Rangers are harried. And a sure way to make sure your children never, ever want to visit a national park again is by packing them in a car and telling them you’re going to visit Yellowstone today—a park that could easily take a week to see in its entirety. And that’s just the frontcountry. Not to speak ill of visitors—we appreciate you all, we really do—but we can easily pick out the ones that have clearly done no research whatsoever. I had a visitor walk up to me when I worked at Old Faithful with a confused look on his face. He said, “Where are the big trees?” I prepared to go into my little pocket program about the lodgepole pines, and why there were so many dead ones. But he interrupted me. “No, I mean, like, the really big trees.” Me (a little perplexed): “We have a petrified tree… is that what you mean?” Him (irritated): “No, the really big, famous trees! The ones everyone takes pictures with! The ones everyone goes to see!” Me (realizing): “Oh. You mean the redwood trees.” Him: “Yes! Where are they?” Me: “Um, California.” Do a little research. With the Internet, there’s no reason not to. You don’t have to learn everything, and it certainly shouldn’t replace talking to a ranger. But getting an idea of the general layout of the park, the main highlights, and what you hope to get out of your trip means that when you do come into a visitor center, you’ll be able to… 2. Specify Visitor centers can be crowded places, with kids screaming for stuff from the bookstores while parents ask about waterfall hikes as Ranger Bob tries to give a raptor presentation in the corner. If you come in and ask me, “what should I do here?” chances are I’m going to take a big deep breath before answering so I can do it with courtesy. Some parks are big, some are little, but they are all diverse, dynamic places. If I had an hour, I couldn’t cover all the things you could do in the park. And I don’t have an hour. At 1 PM on a Saturday in July, I have maybe four minutes, tops—less if there’s a line. I want to give you the best park experience I can, but first I have to know what you’re looking for. (See I wish I was a golem, above.) The most relieving moment for me is when a visitor comes to the desk with a map and a list and says, “We have four days. We’re camping near the South Gate. I have two kids under five who like to hike, but not more than four miles or so. This is what we were thinking of doing—can you give me your thoughts?” She’s given me parameters to work with. She’s anything but a blank slate. She’s looked up a little online, talked to friends, and made notes of what she wants to do. So now I can tell her that sorry, this one trail is closed, but this other one may work well for you. Oh, and if you want to visit this location, I’d do it early so you can avoid the crowds. And if it were me, I’d flip these two days so you can see the bluegrass music we have on Saturday. The other wonderful, glorious, hand-kissingly gratifying thing this visitor has done is to… 3. Allow yourself some time. Another thing that will dismay a ranger is if you come to them and say, “I have an hour. What should I do here?” Here’s the likely answer, borrowed from Yosemite naturalist Carl Sharsmith: “I’d cry.” Unless you’re visiting a small national monument or historic site, there is simply very little you can do in a national park in an hour beyond sitting in traffic. I can potentially point you to the closest highlight of the park, but as I mentioned before, these are crowded places, and those highlights—think Old Faithful, or Clingman’s Dome—are going to be the most crowded places in the park. Parking will be impossible and people will be everywhere. It’s not going to be a pleasant experience. Sometimes we can point you to a quiet trail or lookout nearby where you can take a moment and breathe before getting back in your car. If that’s what you and your family are looking for, tell us so, and we can try to make something work for you. But if you want to see the park’s greatest hits in a short timeframe, you may wish you hadn’t. Allow yourself a little time. Spend a night, stay a while. I had one father and daughter from Brooklyn who spent three days just around our visitor center. They came to each one of my ranger programs and popped up now and again to ask about this hike or that hike. We got to know them so well that on their last day we had the daughter help us feed the pigs and chickens on the farm, and I had her help me take down the flag while her dad took pictures. What a neat experience for a little kid—to pal around with the rangers and have several days to just explore. Breathe. Plan for a few days. Be realistic about time. You’re on vacation. Unfortunately, if you visit during high season, you will probably still be running into crowds no matter how much you plan or how much time you have. So as a ranger, I will often advise folks to… 4. Consider looking outside the national park. I know, I know—a national park ranger telling people to go outside the park. Hear me out. Some national parks are islands in the middle of an urban jungle, but many aren’t. Many are surrounded by other forms of public land—national forests, state parks, wildlife refuges, et cetera. And in lots of cases, these areas are going to be just as beautiful as the national park, and they’re going to see a fraction of the visitation. This is especially useful for folks looking to camp. Some of the cleverest visitors I’ve met are the ones who pitch their tents in the national forest next door, where camping is free and they’ve got the campground to themselves, and then they hike into the park, skipping the lines and vehicle fees (yes, that’s totally legal). Others will use the national forest as their base camp and drive in from there, planning for the added hour or so it may take them to get in the park. If you truly want an off-the-cuff adventure, consider sticking to less traveled places like national forests or state parks. Be prepared on the basics: always fill up on gas when it’s available, always pee when you have the chance, and carry plenty of food and water with you. That will give you a little more wiggle room to explore those backcountry roads and remote areas. And if most of this is news to you, I ask you to please… 5. Dispel with the notion that park rangers are keeping secrets from you. First of all, if there are places you can’t go, unless it’s the employee break room (our safe space), it’s likely we can’t go there, either. The only secret we’ll keep from you is what our favorite restaurant is, to avoid accusations of the park patronizing certain businesses. Don’t think that we as rangers joyfully snigger at visitors having to plod along the boardwalks in the geyser basins while we prance across the sinter cones. We have just as much chance of falling in a hot spring as you, and we are just as vulnerable to mama grizzlies on trails that are closed because of bear cubs, and we cause just as much damage to revegetation zones, and we wait just as long as you in road construction traffic. (I worked with two rangers who were married and worked at two different visitor centers. It was only about 45 minutes between the two centers, but for much of the spring a key bridge was under construction, so instead they were forced to drive five hours around the loop road to see each other. We used to joke about them standing on either side of the bridge and signaling to each other in semaphore, or else playing Frisbee over the river.) We’re not hiding the best places in the park from you. The highlights of the park are highlights for a reason—they’re gorgeous or significant in some way, and they’re easy to get to. Is the view down Cascade Canyon from Lake Solitude to the Teton Group better than the view from popular Inspiration Point? Yes, absolutely, A+, 100%, Would Date. But getting up to Lake Solitude takes eight miles of hiking one-way, whereas Inspiration Point is a short walk from the boat ramp. Most people are looking for the latter. This is why specifying is so helpful (see point 2). If you are looking for things that are off-the-beaten track, tell us so, but don’t expect them to be close by or convenient to get to—that’s why they’re less crowded. If you truly want to be let in on ranger secrets, then you should definitely… 6. Go to a ranger program! Park ranger programs are called “interpretation” (as in, you’re “interpreting” the park for the visitor) and have evolved waaayyy beyond Ranger Frank clicking the button on a slideshow of sedimentary rocks (although we do still have traditional programs like these, and sedimentary rocks can be pretty sweet). A large bulk of our job is researching, developing, and delivering interpretive programs, and we’re going to pull out all the stops to make sure it’s engaging for you and your kids. We know you don’t have to attend our program. We want you to want to attend our program. Even if you have a high level of nature literacy and could hike Mount Rainier blindfolded, you might still be surprised at what you can learn following a ranger on a guided two-mile walk. We’re storytellers by trade. We aim not just to explain, but to inspire and provoke. We design our programs with that guiding principle in mind (throwback to that time a few days ago when I squealed and clapped my hands when one of our interns finally got her copy of Tilden’s Interpreting Our Heritage in the mail). If you walk the south rim of the Grand Canyon, you’re going to see the stone wall along the edge, and you might even know it was built by the CCC. But unless you go on Ranger Molly’s History Walk, you’re going to miss the heart-shaped rock the CCC boys put in the wall right in front of the Harvey girls’ dormitories. There are so many little stories that whisper through the parks. I’ve seen people in tears while listening to a ranger recount the family ties of the inhabitants of Mesa Verde. I’ve seen the Badlands transformed into Narnia and Middle Earth with a ranger who paralleled the otherworldly landscape with those from fiction. I’ve seen kids laugh with delight as the ranger uses her handkerchief to show how Wind Cave “breathes.” And yes, I’ve seen visitors sway and sing along with the ranger by the campfire as he sings “Home on the Range” in Yellowstone while the buffalo do, in fact, roam behind him.

Park rangers aren’t gatekeepers or armed guards. We’re ambassadors for the parks we represent. Come see us. Prepare a little beforehand. Let us know how we can help you. Our goal is to give you the best park experience we can. We want you to leave with fond memories, a greater appreciation for our country’s resources, and a heightened sense of the world around you. We want your kids to believe in the magic and majesty of our public lands. That’s why we do what we do. That’s why we wear the hat. That’s a pretty sweet deal for the price of an entrance ticket.

2 Comments

Friends, I think the only way we make progress is when we stop saying "you, you, you" and start saying "I, I, I."

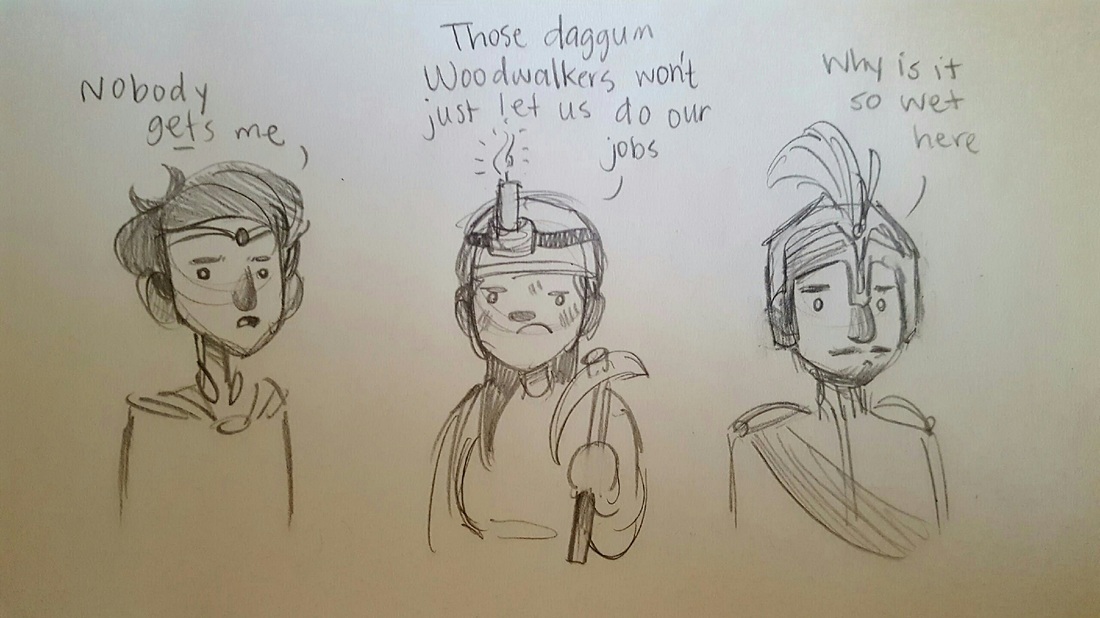

I am racist. I have made assumptions and had disrespectful thoughts based solely on someone's race. I have wrapped myself in my privilege and kept silent. And so... I promise to listen. I promise to take it upon myself to learn, and not force someone to teach me. I promise to believe that someone's pain is real even though it is not my lived experience. I promise to stop and examine myself when I make assumptions and look for justification. I promise to be more inclusive in my home life, in my work, in my parenting, in my writing, and in my art. I promise to work to undo the ramifications of my silence and privilege. This started off as a Facebook post but quickly became much longer and more involved, so I brought it over to the blog instead. I am slowly (veeerrrrrry slowly) garnering reviews on Amazon and Goodreads for Woodwalker. At the beginning of this adventure, I wasn't sure how I was going to approach reviews. Some authors can't bear to look at them, good or bad. Some obsess over each one. I read my first few without actually meaning to---I went to Goodreads to copy a link a few days before the book released, only to find two advanced reviews already up. 4-stars and 5-stars. Nice! My reviews on both sites are still overwhelmingly positive (I'm at 5 stars on Amazon and 4.27 stars on Goodreads, where I have more ratings). But as the weeks have gone by, I've started getting a few not-so-good reviews, too. I've found I approach them in a kind of detached, academic way. Maybe it's the vestiges of grad school--approach all criticism with full consideration. I suspect, though, it has something to do with the fact that the main theme of complaints about Woodwalker are things I've suspected or worried about all along. "A run-of-the-mill adventure...all in all, very mediocre." BAM! Shot through the heart... The cultures in Woodwalker ARE very monolithic, and it drives me crazy, too--I can't stand shallow, lazy worldbuilding. I think in the beginning, I was going for a Lord of the Rings feel, where if you're in Rohan, you know people are going to be good with horses, and if you're in the Shire, you know people are going to be good at gardening and drinking, and if you're in Mirkwood, you know people are going to be good at getting their culture waxed and candy-coated by filmmakers. But as Woodwalker grew, this kind of characterization ended up giving a very one-dimensional effect to each country. Or at least, it appears that way based on the motives of the protagonist and the circumstances of the plot. The Wood Guard is a small, elite portion of the Royal Guard, but because Mae was one herself, they're the main focus of the plot. Pearl-diving in Lumen Lake is more of a cultural thing, like football or defacing National Parks over summer vacation--during their independence, there are some people who would dive professionally, but many more are doing the things a country needs to thrive--being merchants, artisans, farmers, politicians, homemakers, etc. But because the country is now under Alcoran control, and because Alcoro is only interested in pearl exportation, the setup of the country has been reconfigured to revolve solely around diving. So on the one hand, yes, the protagonists do tend to reflect the main activities and mindsets of each country, but on the other hand, if the story was narrated by, say, King Valien, or a Silverwood silver miner, or an Alcoran soldier, we'd get much different views of each country. I don't write this as a response to the people who didn't enjoy my book. The more people who read it, the more mixed reviews I'll get, and many will be far less polite than the few I've gotten already. I'm preparing for that. But, this is why reviews are so important. I love hearing that people enjoyed the book. But I also like looking at the common threads that pop up and then taking a critical eye to my current and future manuscripts and saying, "how can I make this better?"

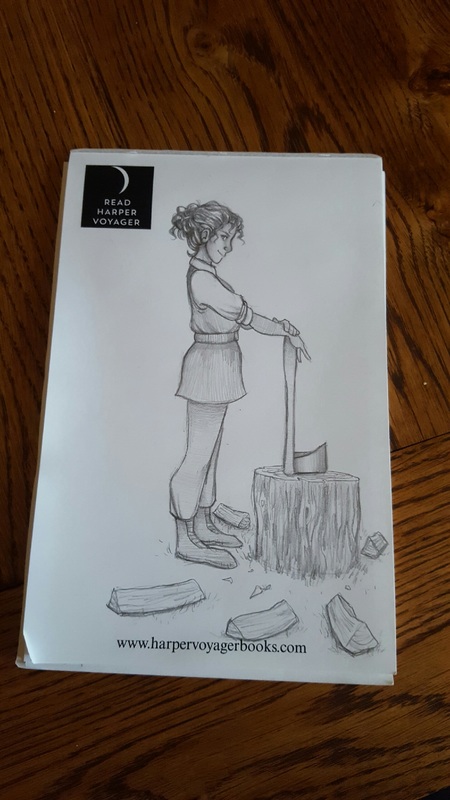

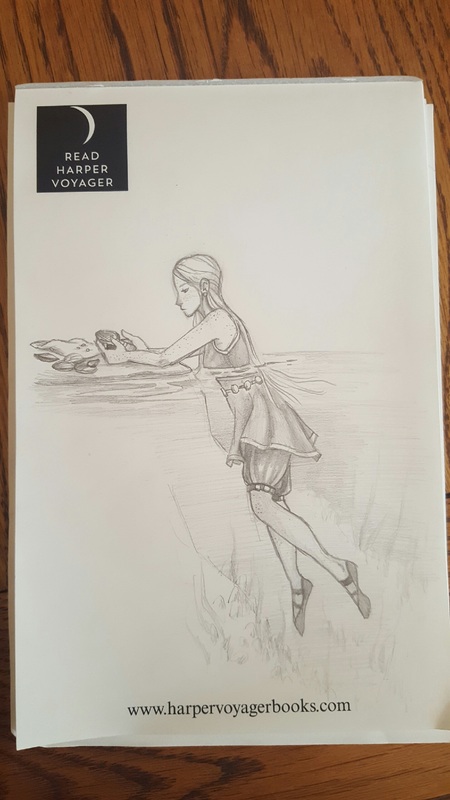

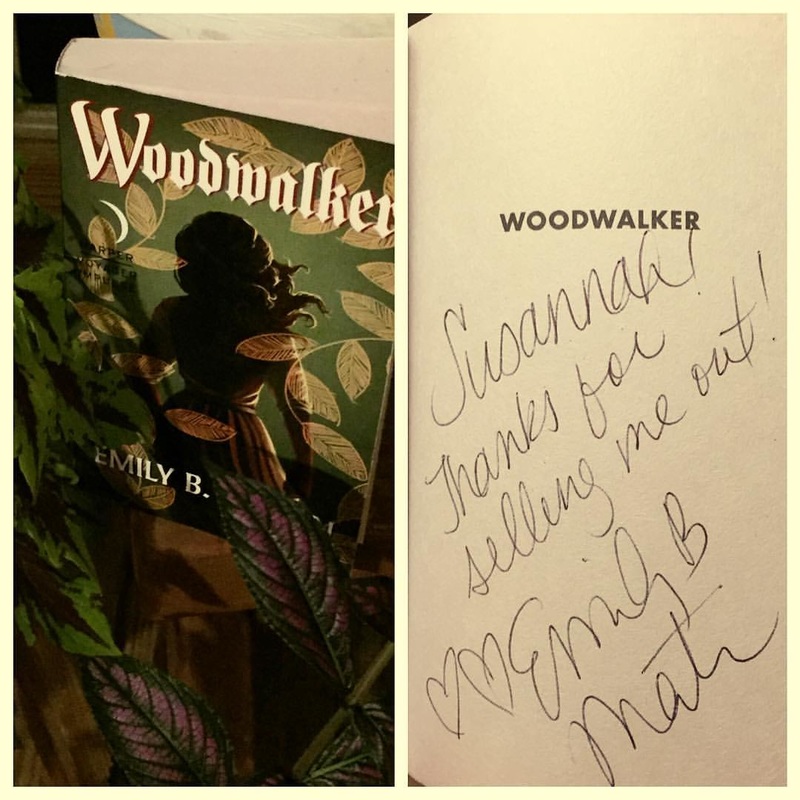

And not everything is going to be relevant. Some people, like my mom, are so totally blindsided by the plot twist that they have to go back and read the thing again to see the clues I laid down for it. Others see it coming from chapter one. That's just a difference in readership, and that's not something I need to rework. My books won't be for everyone. That's okay. But hopefully I can make a concerted effort to think a little more holistically with each manuscript I write. The moral of the story is: PLEASE LEAVE REVIEWS. PLEEA-HE-HE-HEEEAAASE We had a party! A big book party! After weeks of planning and a day of near misses (including a rushed attempt to close on our old house, a torrential downpour while I loaded the car, and a frightening hydroplane in rush-hour Easley traffic) we threw Woodwalker a big old party! The event was at M.Judson Booksellers, a fantastic bookstore/café located in the old historic courthouse in downtown Greenville. We set up several big posters, a slideshow of artwork, and the signpost my dad made from chapter two of Woodwalker. Things started off with some unscheduled time—I sat and signed books while folks took a look around the bookstore, colored pictures, and ate cupcakes made by the wizardly hands of the Chocolate Moose staff. We also had a raffle going on—folks could donate a dollar for a ticket to win a prize package of book paraphernalia, including a tote bag and poster printed with Mae’s mantra, “One crisis at a time,” a copy of the book that I had sketched in, and a handful of bookmarks and stickers. All the money went into a box to donate to Friends of the Smokies, a nonprofit organization that supports Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which is where I work as a park ranger, and which served as the inspiration for the main setting in Woodwalker After some free-range time, we gathered together. I said a few special thank you’s and then launched into a short reading and discussion on Woodwalker’s protagonist, Mae. I’m used to standing up in front of crowds of people and talking—it accounts for roughly a third of my job, after all. But I’m usually expounding on the virtues of some natural or historic treasure, so talking about my own work was weird. I think I chose the wrong passage to read—I’ve heard it pays to pick an action-oriented scene, and if I could do it over again, I’d have chosen Mae’s encounter with the bear over her dialogue bit with Arlen. I also read too fast—my friend recorded me reading, and as soon as I saw the video I curled up on myself, twitching, like a dying cockroach. Listening to oneself speak is AWFUL. But necessary. Speaking too fast has always been an issue for me in my ranger programs. Time to work on dialing it back again. Fortunately we moved on to Q&A, during which people asked some great questions, including a question about whether the plants and animals in the book are all real (answer: yes), so I got to put on my ranger hat (not really, I can’t wear it out of uniform) and talk a little bit about the book's fireflies and plants that are all native to the Smokies. Someone else asked about my motivation behind making my protagonist a heroine, to which I talked about my desire for “girl Aragorn where it doesn’t matter that she’s a girl” and about the heroines I might want my own daughters to read about as they grow up. And then several people were curious about a sequel, to which the answer is YES! In January (probably). We closed things out with the raffle drawing. I had my four-year-old Lucy pull a ticket out of the jar. She picked my dad’s ticket! He said to pick another one. So I gave the jar to my two-year-old Amelia. She pulled out a fistful and then picked her favorite one. The tote bag, poster, and illustrated book went to a long-time family friend, Jackie. Some of the coolest moments of the nights were the ones I didn’t expect. My high school art teacher and chemistry teacher showed up—and my chemistry teacher brought with her a picture book I’d written for a Mole Day project in her class! It’s been twelve years since I was in her class, and she’s kept it all this time! My art teacher also nudged me about another picture book I had illustrated for my senior project in her class. I felt so fortunate not just to have had so many fantastic teachers in my life, but to have ones who have followed and supported my work. I had old friends from high school show up, some of whom drove several hours to be there. My college roommate, my financial adviser, my in-laws, and many honorary aunts and uncles… so many people turned up to celebrate. I met new friends from local library systems, friends-of-friends, and people who just happened to wander in during the event. I loved seeing everybody hanging out, coloring pictures, and talking about books. I especially loved the moment when the event coordinator, Mary, sidled up to me to inform me she’d sold out of books. My sweet friend Susannah had bought her very last copy. Thanks to everyone who came out and made this event so special. Thanks for supporting me and Woodwalker every step of the way. Thanks for your kind words about the book itself and your interest in the futures of Mae, Mona, and the other protagonists! See you guys again in January 2017 for round two! |

Emily B. MartinAuthor and Illustrator Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed