|

Thanks to a summer of posting ranger photos and hashtags, I’ve had quite a few people get in touch to ask about becoming a park ranger. Since I’ve already scrambled this summer’s blog post topics anyway, I decided to take a detour from my usual posts and reflect a little on this season and the many routes to get into the coveted flat hat.

All statements and opinions are my own and are not endorsed or maintained by the National Park Service. All photos are my own. Read it all after the jump!

2 Comments

It's summer again, which means it's time to take the flat hat out of storage and head into the wilderness for four months. I will be spending my summer working with the National Park Service again, and my WiFi will be limited. I am working to keep my social media feeds updated, but blog posts will be few and far between. Please follow me elsewhere for updates throughout the summer!

Projects I'll be tackling:

Follow me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (@EmilyBeeMartin) to keep up with all this and more! I can’t believe how fast the summer is going. In just another few weeks, our interns will leave, kids will go back to school, and visitation in Great Smoky Mountains National Park will scale back dramatically, at least until leaf season in October. It’s been a great season full of bug-hunting in the river with Junior Rangers, telling stories on the Mountain Farm, and shaking our fists at the elk standing defiantly in the garden eating acorn squash. But I’ve been keeping a list. I started this list last year in Yellowstone. It’s hard not to. So much of a front-line park ranger’s job is visitor services that we quickly figure out how to get to the bottom of what a visitor is looking for in their park experience. I’m currently reading The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker, where the golem can sense other people’s wants and desires. I can’t think of another superpower I would rather have when a visitor comes to the desk, tells their kids to hush, and asks me, “What is there to do here?” I’ve compiled a few suggestions for folks planning to travel—anywhere, really, but especially to your national parks. It’s not exhaustive. I’m sure other rangers at different parks could chime in with a thousand more things. But these are some basics to keep in mind when planning your trip. 1. DO PLAN YOUR TRIP I think there is a very romantic idea in people’s heads about hopping in the car with a full tank of gas and half a pack of cigarettes and embarking on a spur-of-the-moment Great American Road Trip. I doubt this method worked well even in the Halcyon Days of Route 66, but it works even less well now, despite what Instagram will have you believe. National parks, at least at high season, are crowded places. Campgrounds fill up. Entrance lines are long. Rangers are harried. And a sure way to make sure your children never, ever want to visit a national park again is by packing them in a car and telling them you’re going to visit Yellowstone today—a park that could easily take a week to see in its entirety. And that’s just the frontcountry. Not to speak ill of visitors—we appreciate you all, we really do—but we can easily pick out the ones that have clearly done no research whatsoever. I had a visitor walk up to me when I worked at Old Faithful with a confused look on his face. He said, “Where are the big trees?” I prepared to go into my little pocket program about the lodgepole pines, and why there were so many dead ones. But he interrupted me. “No, I mean, like, the really big trees.” Me (a little perplexed): “We have a petrified tree… is that what you mean?” Him (irritated): “No, the really big, famous trees! The ones everyone takes pictures with! The ones everyone goes to see!” Me (realizing): “Oh. You mean the redwood trees.” Him: “Yes! Where are they?” Me: “Um, California.” Do a little research. With the Internet, there’s no reason not to. You don’t have to learn everything, and it certainly shouldn’t replace talking to a ranger. But getting an idea of the general layout of the park, the main highlights, and what you hope to get out of your trip means that when you do come into a visitor center, you’ll be able to… 2. Specify Visitor centers can be crowded places, with kids screaming for stuff from the bookstores while parents ask about waterfall hikes as Ranger Bob tries to give a raptor presentation in the corner. If you come in and ask me, “what should I do here?” chances are I’m going to take a big deep breath before answering so I can do it with courtesy. Some parks are big, some are little, but they are all diverse, dynamic places. If I had an hour, I couldn’t cover all the things you could do in the park. And I don’t have an hour. At 1 PM on a Saturday in July, I have maybe four minutes, tops—less if there’s a line. I want to give you the best park experience I can, but first I have to know what you’re looking for. (See I wish I was a golem, above.) The most relieving moment for me is when a visitor comes to the desk with a map and a list and says, “We have four days. We’re camping near the South Gate. I have two kids under five who like to hike, but not more than four miles or so. This is what we were thinking of doing—can you give me your thoughts?” She’s given me parameters to work with. She’s anything but a blank slate. She’s looked up a little online, talked to friends, and made notes of what she wants to do. So now I can tell her that sorry, this one trail is closed, but this other one may work well for you. Oh, and if you want to visit this location, I’d do it early so you can avoid the crowds. And if it were me, I’d flip these two days so you can see the bluegrass music we have on Saturday. The other wonderful, glorious, hand-kissingly gratifying thing this visitor has done is to… 3. Allow yourself some time. Another thing that will dismay a ranger is if you come to them and say, “I have an hour. What should I do here?” Here’s the likely answer, borrowed from Yosemite naturalist Carl Sharsmith: “I’d cry.” Unless you’re visiting a small national monument or historic site, there is simply very little you can do in a national park in an hour beyond sitting in traffic. I can potentially point you to the closest highlight of the park, but as I mentioned before, these are crowded places, and those highlights—think Old Faithful, or Clingman’s Dome—are going to be the most crowded places in the park. Parking will be impossible and people will be everywhere. It’s not going to be a pleasant experience. Sometimes we can point you to a quiet trail or lookout nearby where you can take a moment and breathe before getting back in your car. If that’s what you and your family are looking for, tell us so, and we can try to make something work for you. But if you want to see the park’s greatest hits in a short timeframe, you may wish you hadn’t. Allow yourself a little time. Spend a night, stay a while. I had one father and daughter from Brooklyn who spent three days just around our visitor center. They came to each one of my ranger programs and popped up now and again to ask about this hike or that hike. We got to know them so well that on their last day we had the daughter help us feed the pigs and chickens on the farm, and I had her help me take down the flag while her dad took pictures. What a neat experience for a little kid—to pal around with the rangers and have several days to just explore. Breathe. Plan for a few days. Be realistic about time. You’re on vacation. Unfortunately, if you visit during high season, you will probably still be running into crowds no matter how much you plan or how much time you have. So as a ranger, I will often advise folks to… 4. Consider looking outside the national park. I know, I know—a national park ranger telling people to go outside the park. Hear me out. Some national parks are islands in the middle of an urban jungle, but many aren’t. Many are surrounded by other forms of public land—national forests, state parks, wildlife refuges, et cetera. And in lots of cases, these areas are going to be just as beautiful as the national park, and they’re going to see a fraction of the visitation. This is especially useful for folks looking to camp. Some of the cleverest visitors I’ve met are the ones who pitch their tents in the national forest next door, where camping is free and they’ve got the campground to themselves, and then they hike into the park, skipping the lines and vehicle fees (yes, that’s totally legal). Others will use the national forest as their base camp and drive in from there, planning for the added hour or so it may take them to get in the park. If you truly want an off-the-cuff adventure, consider sticking to less traveled places like national forests or state parks. Be prepared on the basics: always fill up on gas when it’s available, always pee when you have the chance, and carry plenty of food and water with you. That will give you a little more wiggle room to explore those backcountry roads and remote areas. And if most of this is news to you, I ask you to please… 5. Dispel with the notion that park rangers are keeping secrets from you. First of all, if there are places you can’t go, unless it’s the employee break room (our safe space), it’s likely we can’t go there, either. The only secret we’ll keep from you is what our favorite restaurant is, to avoid accusations of the park patronizing certain businesses. Don’t think that we as rangers joyfully snigger at visitors having to plod along the boardwalks in the geyser basins while we prance across the sinter cones. We have just as much chance of falling in a hot spring as you, and we are just as vulnerable to mama grizzlies on trails that are closed because of bear cubs, and we cause just as much damage to revegetation zones, and we wait just as long as you in road construction traffic. (I worked with two rangers who were married and worked at two different visitor centers. It was only about 45 minutes between the two centers, but for much of the spring a key bridge was under construction, so instead they were forced to drive five hours around the loop road to see each other. We used to joke about them standing on either side of the bridge and signaling to each other in semaphore, or else playing Frisbee over the river.) We’re not hiding the best places in the park from you. The highlights of the park are highlights for a reason—they’re gorgeous or significant in some way, and they’re easy to get to. Is the view down Cascade Canyon from Lake Solitude to the Teton Group better than the view from popular Inspiration Point? Yes, absolutely, A+, 100%, Would Date. But getting up to Lake Solitude takes eight miles of hiking one-way, whereas Inspiration Point is a short walk from the boat ramp. Most people are looking for the latter. This is why specifying is so helpful (see point 2). If you are looking for things that are off-the-beaten track, tell us so, but don’t expect them to be close by or convenient to get to—that’s why they’re less crowded. If you truly want to be let in on ranger secrets, then you should definitely… 6. Go to a ranger program! Park ranger programs are called “interpretation” (as in, you’re “interpreting” the park for the visitor) and have evolved waaayyy beyond Ranger Frank clicking the button on a slideshow of sedimentary rocks (although we do still have traditional programs like these, and sedimentary rocks can be pretty sweet). A large bulk of our job is researching, developing, and delivering interpretive programs, and we’re going to pull out all the stops to make sure it’s engaging for you and your kids. We know you don’t have to attend our program. We want you to want to attend our program. Even if you have a high level of nature literacy and could hike Mount Rainier blindfolded, you might still be surprised at what you can learn following a ranger on a guided two-mile walk. We’re storytellers by trade. We aim not just to explain, but to inspire and provoke. We design our programs with that guiding principle in mind (throwback to that time a few days ago when I squealed and clapped my hands when one of our interns finally got her copy of Tilden’s Interpreting Our Heritage in the mail). If you walk the south rim of the Grand Canyon, you’re going to see the stone wall along the edge, and you might even know it was built by the CCC. But unless you go on Ranger Molly’s History Walk, you’re going to miss the heart-shaped rock the CCC boys put in the wall right in front of the Harvey girls’ dormitories. There are so many little stories that whisper through the parks. I’ve seen people in tears while listening to a ranger recount the family ties of the inhabitants of Mesa Verde. I’ve seen the Badlands transformed into Narnia and Middle Earth with a ranger who paralleled the otherworldly landscape with those from fiction. I’ve seen kids laugh with delight as the ranger uses her handkerchief to show how Wind Cave “breathes.” And yes, I’ve seen visitors sway and sing along with the ranger by the campfire as he sings “Home on the Range” in Yellowstone while the buffalo do, in fact, roam behind him.

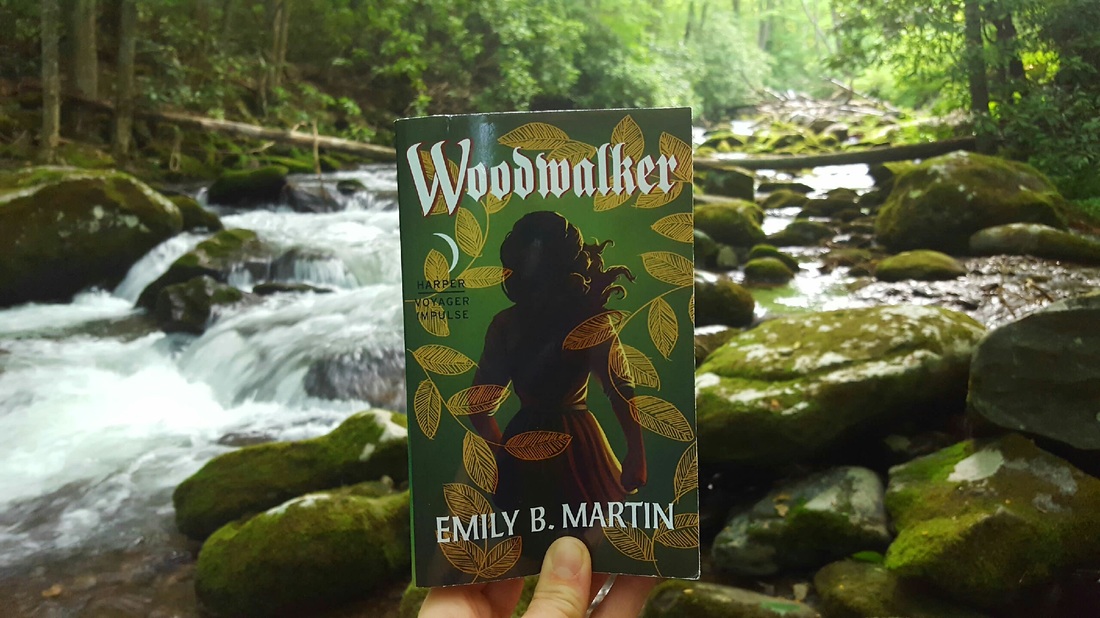

Park rangers aren’t gatekeepers or armed guards. We’re ambassadors for the parks we represent. Come see us. Prepare a little beforehand. Let us know how we can help you. Our goal is to give you the best park experience we can. We want you to leave with fond memories, a greater appreciation for our country’s resources, and a heightened sense of the world around you. We want your kids to believe in the magic and majesty of our public lands. That’s why we do what we do. That’s why we wear the hat. That’s a pretty sweet deal for the price of an entrance ticket. Tomorrow my paperback releases. Several months ago, I asked my editor if I should be planning some kind of launch party. He replied with an emphatic yes, that this was an accomplishment worth celebrating. I worried a little bit because I knew that at the time of my release, I wasn’t going to be at home—I was going to be several hours away in Great Smoky Mountains. I couldn’t really throw the kind of party he was thinking of.

But tonight something wonderful and spontaneous happened. A whole bunch of us rangers got together for a bonfire and s’mores, swapping stories of other parks we’d been in and geeking out about interpretation. And then, in a sort of spur of the moment kind of decision, several of us decided to drive to a nearby trailhead, where we’d heard reports that our native synchronous fireflies had been flashing. Woodwalker is set in a fantasy southern Appalachia. The Silverwood Mountains are the Great Smoky Mountains. And to Mae and her folk, firefly season is a sacred time full of celebration and reverence. So it struck me, as I walked up the trail in the dark with my fellow rangers, that this was, in fact, the greatest way I could have chosen to celebrate Woodwalker’s release. We reached a bend in the trail, near a patch of that damp, open woodland the fireflies like so much, and we were met with a dazzling wave of synchronized light flashing through the forest. Six, seven, eight bursts of coordinated flashing, and then darkness, like the flick of a lightswitch, and then a few seconds later—they began again. And the evening fireflies were out, swooping yellow with each blink. The flashbulbs were out, their strobe-light lanterns so bright they cast visible shadows on the path. And my favorite—and Mae’s favorite—the blue ghosts, were out, drifting gently among the flickering and flashing, glowing that soft, moonlight blue. I am filled with gratitude for everyone who has helped and encouraged me along this journey—my family, my friends, my agent, my editor, my publicist, my fellow Harper Voyager authors whose camaraderie means so much to me. And I’m filled with gratitude simply to this place, and to these bugs, and the pillowed moss and the curling mist and the tumbling creeks that have saturated Woodwalker with so much life. Magic exists, and it exists here in these hills. It’s that time of year again. Summer. Travel season. When vacations planned years in advance finally come together. The kids are out of school. It’s time for families to take some time and just be together. It’s time to create memories everybody can share further down the line.

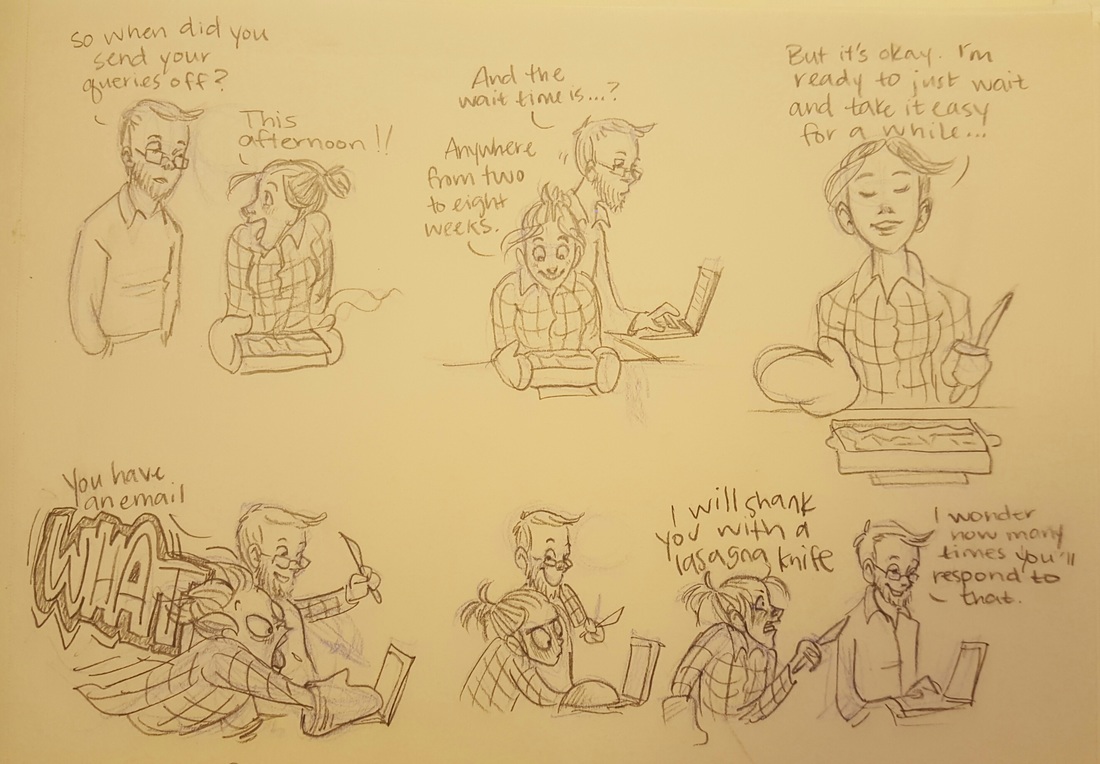

For me, though, summer is starting to mean the opposite. Summer is when I pack my suitcase, get my ranger uniform out of storage, and leave my family behind. My life as a stay-at-home mom transitions abruptly—not just into being a working parent, but being a working parent far away from my husband and daughters. It’s not as extreme as it sounds. Last summer, I spent a month on my own in Yellowstone before my husband and kids came out to spend the summer with me. They aren’t able to stay with me this summer, but being in Great Smoky Mountains means I am only two hours from home. They are visiting right now—the kids are napping on the couch cushions spread on the floor of the living room, since I only have one bedroom. So it’s not so bad. Some people face much more intense separations from their family for much longer lengths of time. But that doesn’t make saying goodbye any easier, and it certainly doesn’t alleviate the significant level of guilt I feel as I drive away from my husband—left alone to be a single parent, and my kids—without their mom for a chunk of the summer. I have gotten pretty good at driving while crying. I usually end up holding lengthy conversations with myself to talk through this decision to put my two degrees in park management and visitor services to use. They often start with the same questions. Why am I doing this? Is it really worth it? I have my degrees my whole life—my kids are only young once. Is it unfair to them? Will they be sad? Will they miss me? What if they don’t miss me? Will they behave for their daddy? Is it unfair to him? At least when I stay home during the school year, he comes home at night. He says it’s okay, that he likes having the chance to spend more time with the girls than he does during the rest of the year, but is this going overboard? Those other moms at church—the ones who homeschool their children and teach Sunday School and host juice and cookie parties—they wouldn’t do this to their families. Their families are more important to them than a career. And that’s right, isn’t it? That’s how it should be for a mother. At the most recent goodbye, when I pulled out of the driveway for the Smokies, this narrative got me through civilization and into the national forests at the state line. The sprawl of urban South Carolina gave way to the Chattooga River and the evening light of the Georgia mountains. The land began to rise and fold. I wound up, up the steep road through Flowers Gap while the Avett Brothers serenaded from my speakers, I just want my heart to be true, and I just want my life to be true, and I just want my words to be true—I want my soul to feel brand new. Shifted into low gear on the far side and careened down, down, flanked on all sides by the emerald swells of the Appalachian foothills. Turned north to Cherokee. It’s no secret that this landscape is magic to me. I wrote an entire novel romanticizing the mountains and the culture and the flora and fauna. Heck, I sanctified our native fireflies. And here in the Smokies, we’re in the thick of firefly season! I get to give a ranger talk to people who have traveled from far and wide to see them! The synchronous fireflies, the evening and flashbulb fireflies, the blue ghosts—my favorite—I get to be the cover band for folks riding the trolleys to see them. The Catawba rhododendrons are blooming at high elevation—bursts of ostentatious purple-pink amid all the green. Women’s Work festival is coming in a few weeks—women will stream into the farm to show visitors how to spin yarn, cook on a hearth, and forage the forest for medicinal herbs. My programs on mountain farm life, birdsong, and stream creatures have to be researched. I’m surrounded by ranger hats! Surrounded by the background chatter of the park radio, the rooster screeching down on the farm. Kids bringing me their Junior Ranger books, ready to show me their work and be officially sworn in and given their badge. My family got to be here for my first day back in uniform. As I got ready to head out the door, Amelia put a Frisbee on her head and said she was a park ranger. Lucy has already learned to identify mountain laurel and veeries, just as quickly as she learned aspen trees and ravens last summer. They leave tomorrow, and I’ll spend my days in uniform and my nights writing and drawing (except when I’m with the fireflies). During the week, I’ll Skype with them and hear about how they got to go to the hardware store and how Dad had a surprise for them and it was pudding! And then on my next set of lieu days, I’ll drive back down to see them. And do it over again. The goodbyes might get easier throughout the summer—but I doubt it. Despite this, I am happy with what my family has chosen to do with our summers. I was happy about it last year, and I’m happy about it this year. There are sacrifices to any lifestyle. Because I have a family, because I have kids who will be in school and a husband with a solid job, I know I will not be pursuing a full-time ranger position, not for a long time, if ever. I will be working seasonally long after my colleagues have landed permanent jobs or moved on to a more stable field. But I’m happy with that, too. And I’m happy to think about where we might go in the future—what new places and exciting adventures might become just another part of my kids’ childhoods. Last year it was seeing Old Faithful erupt every day. This year it’s probing deep into the rich forests of southern Appalachia. That, to me, is worth it—even if we have to say goodbye for a little while to make it happen. The "how I got my agent" post is a traditional rite-of-passage for any aspiring author, so here we go. When I first heard from my agent, I was a ranger at Yellowstone for the summer, focusing mainly on telling people when Old Faithful was going to erupt and trying not to be murdered by the most murder-y park in the NPS [citation needed]. That was in 2015. Woodwalker came out in the spring of 2016, and its companion will be out in early 2017. But signing with an agent was my first huge step forward. The first, and potentially most significant.

The story about how I got my agent is, perhaps, no more intriguing than anybody else’s, except there were probably more bison involved than most. Here’s more or less how it went, written inexplicably in second-person.

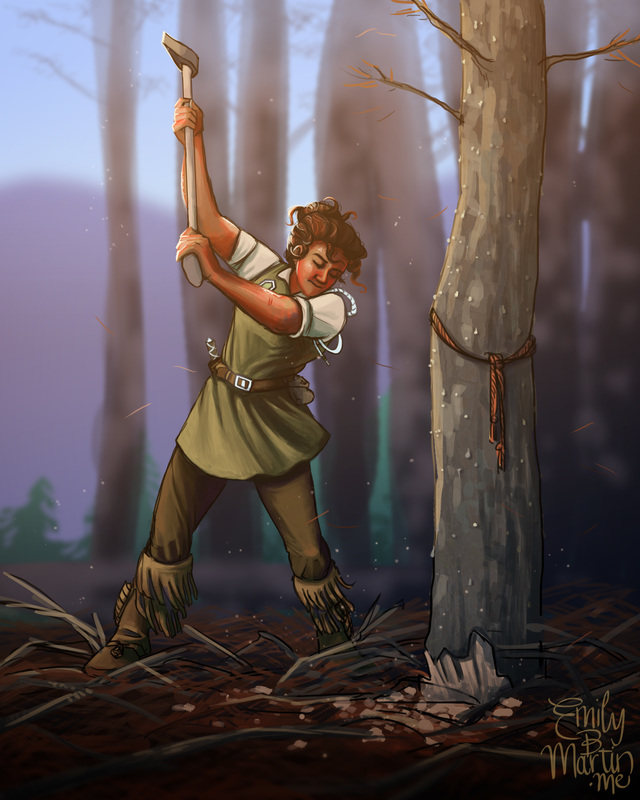

To everyone still in the grips of querying—there’s no advice I can give you that you haven’t already read a hundred times over. Keep at it. Keep writing. Make a point of connecting with people going through the same journey. Vent (but not unprofessionally). Cry (long and hard). Rejoice (longer and harder). And stay the hell away from bison, because seriously, all they want is to see you suffer. “What are you doing?” I’m a park ranger, traipsing along in the footsteps of John Muir and Stephen Mather and the like. And a lot of people, most notably my family, have accused me of casting myself as Mae. This irks me, because it means I’ve committed the most rookie of all mistakes—just writing oneself as the protagonist, rather than creating a unique character. I thought I had left those days behind in middle school. But beyond this, it irks me because Mae’s job is different from mine. She is, at heart, a conservationist rather than a preservationist. Responsible use of resources over preservation for the sake of preservation. In fact, this is why I chose October 4th as her birthday—the death date of oft-maligned Gifford Pinchot, father of modern forestry, with the thought that she’s continuing his work. Granted, Mae has a heart for the inherent worth of wilderness that Pinchot is often accused of lacking (she probably would have been on John Muir’s side over the damming of Hetch Hetchy valley), but her job as a Woodwalker is ultimately to oversee responsible use of the Silverwood’s resources. This is a society not merely passing through a stand of wildland as visitors, but living intimately in it and relying on it for their survival. As such, preservation probably isn’t even a concept the folk of the Silverwood are concerned about. Now, the Silverwood will have been practicing silviculture and forestry much longer than post-European United States, and as such, they’ll have graduated out of some of Pinchot’s more outdated ideas (such as restricting wildfires at all costs). The Wood Guard would oversee strategic timbering to reduce the spread of blight or infestation and would monitor wildfires to facilitate forest regeneration. So that’s what Mae is doing in the illustration above—felling a pine that has fallen prey to pine beetles. And this is where we hop to another, less famous chapter in the history of forestry and land use—the Women’s Land Army and the Women’s Timber Corps. These two organizations, like many others involving women in unusual workplaces, emerged during the First and Second World Wars. The two mentioned were in Britain, but there was also a Women’s Land Army of America and an Australian Women’s Land Army. Their work was closely related to entities like the US Forest Service, but I bring up these lesser-known organizations because the illustration above is referenced directly from a photo of a lumberjill in the Women’s Timber Corps. As famine loomed in Britain in World War I, women were hurriedly recruited to fill agriculture and forestry jobs the soldiers had left behind. They were recruited again during World War II. Once each war was over and the men returned home, the organizations were disbanded—yet another instance of women being ushered into a workforce to compensate for a lack of men, only to be kicked out when the need was gone (or, in the case of the National Park Service, when word got round to Washington that women were working as rangers). And despite the amount of timber the Women's Timber Corps provided for the war effort, they were given no recognition for their work until 2007, when a memorial was erected in Scotland. The Wood Guard is decidedly coed, as with any other profession and industry in the world of Woodwalker. Women serving as foresters or soldiers or politicians is so normal as to be beyond comment. This is perhaps the biggest fantasy element in Mae’s world. But I hope Mae serves as a little homage to these women, continuing their work for the good of her people and her love for her home.

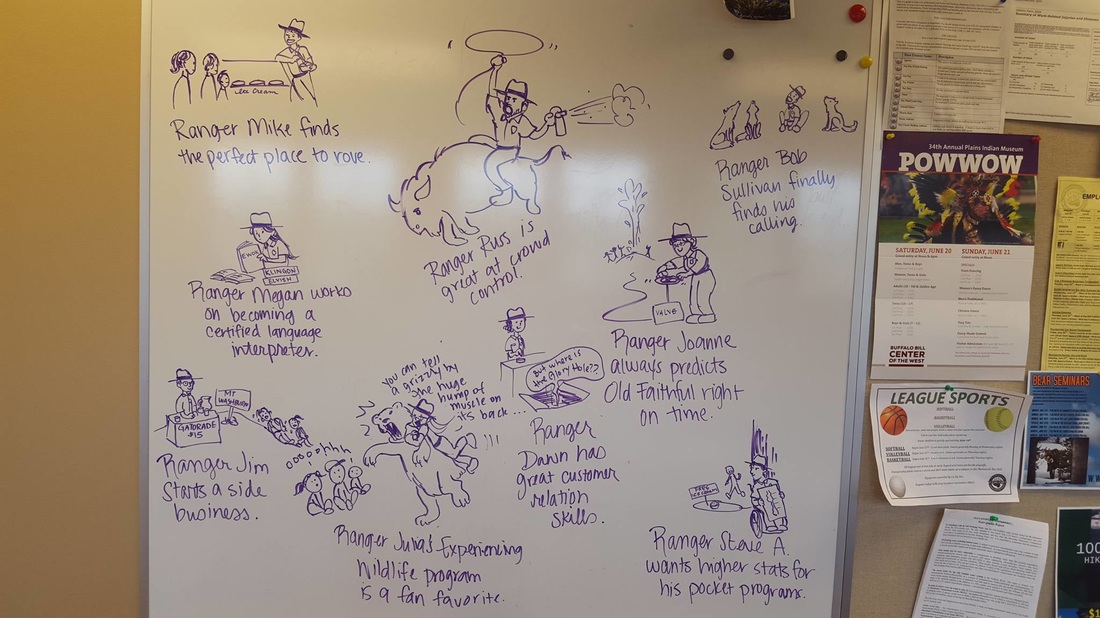

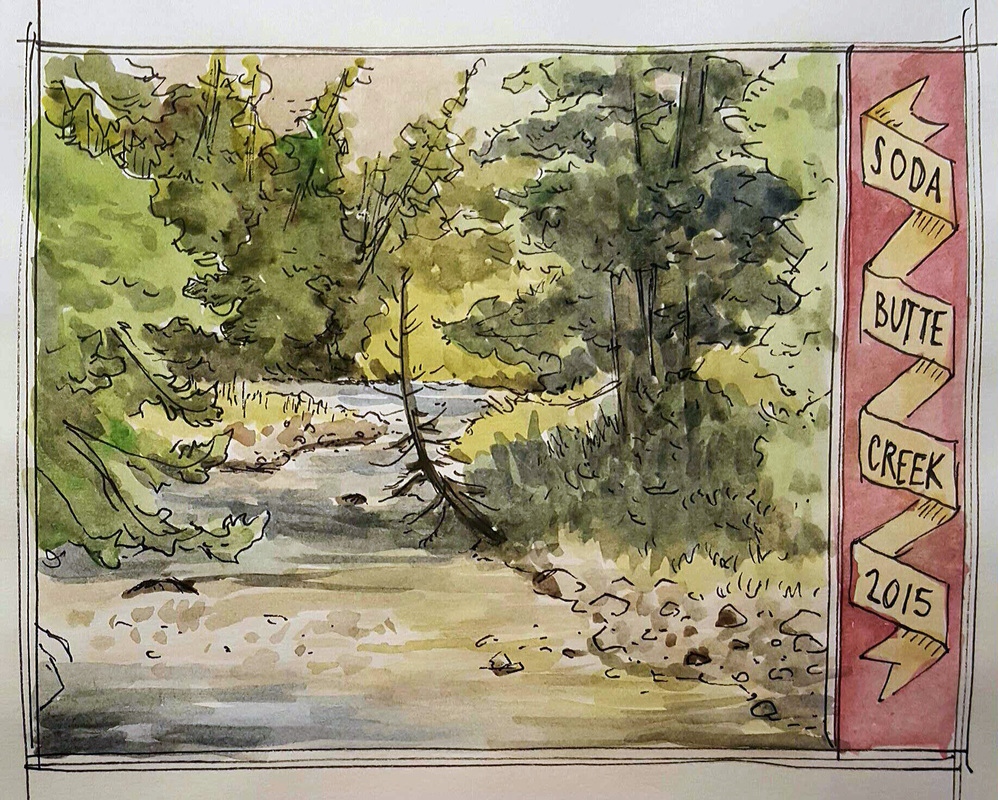

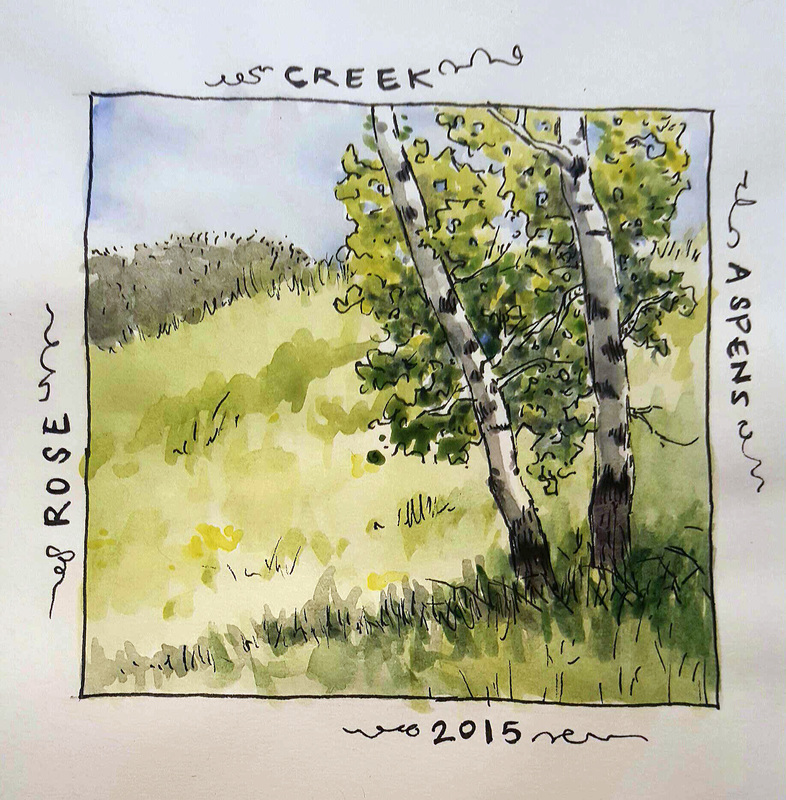

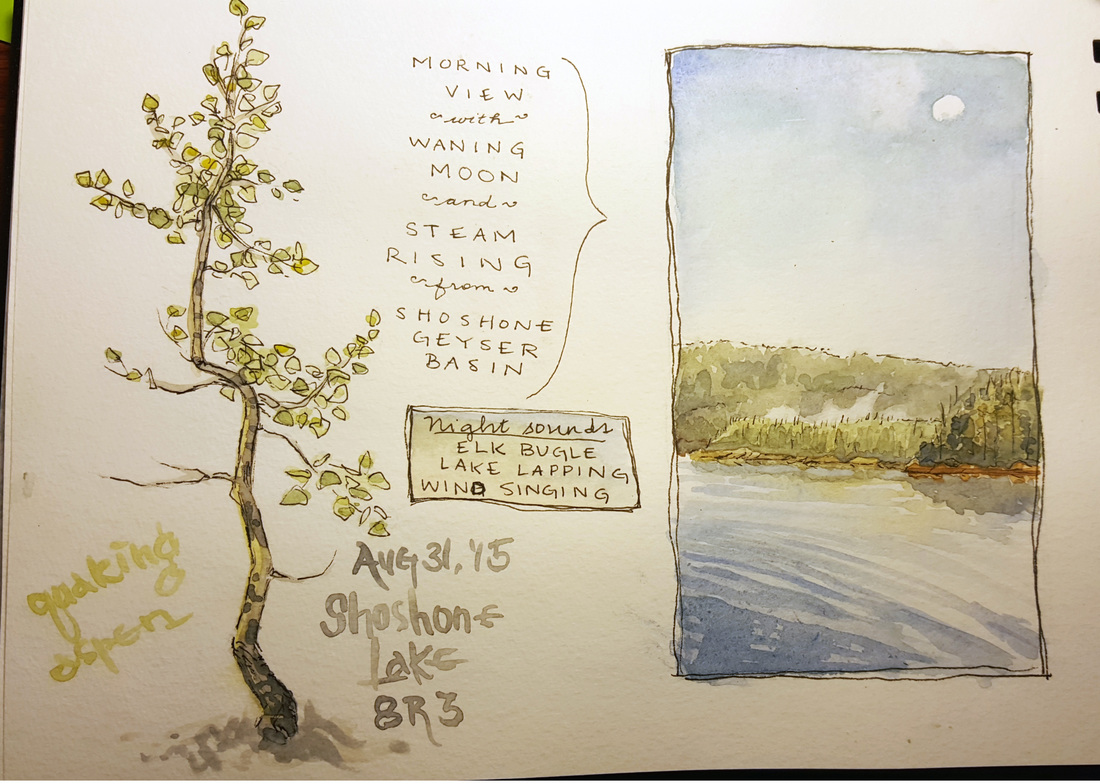

I realize few people care about the differences between a park ranger and a forester, or a preservationist and a conservationist, but Mae is unquestionably more akin to the latter. With some exceptions, her convictions align more closely with Pinchot’s than Muir’s, and her work aligns more closely with that of the women of the Timber Corps and modern foresters than park rangers. In this sense, Mae resembles my conservationist friends building trail at Philmont Scout Ranch or the vegetation crews working to control hemlock woolly adelgids in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Which apparently means I've written fanfiction about my friends, rather than myself. While in Yellowstone, I had the amazing opportunity to take a watercolor sketchbook class up in Lamar Valley. This was a free perk of being a park ranger, and it was one of my favorite experiences of the whole summer. In the height of August, when we were nearly seeing 12,000 people through the visitor center every day, I got to run away to the Lamar Buffalo Ranch and spend three days sketching landscapes. I’d always been a little terrified of watercolors. They just seemed really uncontrollable. But our instructor, Suzie Garner (you can find her on Twitter @suzie_garner), helped me embrace their looseness and unpredictability. Now I’m totally in love with the freshness of watercolors, and how easy it is to throw down my paints and projects mid-stroke and pick it all back up a few hours later (this is immensely helpful when there’s some crisis with the kids). I started bringing my little sketchbook with me all over Yellowstone, even backpacking in the Tetons and along Shoshone Lake. Sitting and painting the landscape is so immersive, and looking back at my sketches plants me right back in that experience. When I look at my favorite sketch below, I remember exactly how still the lake was that morning, how we heard elk bugling across the water, and how the steam curled up from the geyser basin. Gah! An all-inclusive memory. Sometimes I feel like my life is broken up into chapters just like my novels. The chapter that just finished was a big one—my summer out in Yellowstone National Park. After three years of almost exclusively staying home with my girls, it was so, SO incredible to get back into my field in one of the most prestigious visitor centers in the National Park Service. Old Faithful is crazy, guys. Like, holy cow, there would be days where I’d stop to draw breath and realize I hadn’t stopped talking to visitors for an hour and a half. As a result, the people who work there have to be totally on top of everything. I was so fortunate to work with some of the most knowledgeable, dedicated people in my field. People often think of a park ranger job as running around the vast wilderness communing with eagles or whatever, but the truth is, it’s very much a customer service job. And our staff at Old Faithful was a well-oiled machine. Through bear scares, irate visitors, bison jams, and six million Junior Ranger booklets, my fellow rangers were totally immersed in connecting visitors to the park. I learned a lot from every one of them. But more than that, I made some amazing friendships! Hey Rangers! Here’s to next year—the big 1-0-0!!

|

Emily B. MartinAuthor and Illustrator Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed