|

This evening I experienced what has been, so far, the most fulfilling moment of my fledgling career as an author. I had a book signing at our local Books-a-Million, and I signed and sold a decent number of copies. Things started off slow, so I had ample time to sketch in between interested readers. Behind me was the poster I put together showcasing the five main characters of WOODWALKER—Mae, the protagonist, Mona, Colm, Arlen, and Valien. Sketching is often a good way to draw people in, and it worked for a mother and her two twin daughters, probably ten years old or so. They came to see what I was doing and exclaimed over the picture of Mae I was doodling. They asked about the book, and while they were a few years younger than the intended audience, I told them about how it was an adventure story starring a girl, which got them excited. They begged their mom to buy the book, and she agreed, saying that even if it was a little old for them, at least they would learn some new vocabulary words. After I wrote their names in the book and signed it, I showed them the picture I had been drawing again. “She’s the main character,” I said. And I pointed behind me at the poster, which is full color. “And that’s her, too.” “Girls,” said their mother. “Look at her skin.” The two girls looked at the poster and saw that Mae’s skin was brown like theirs. One of them looked back at me and put her arm around my shoulder. “Can I give you a hug?” she asked. I hugged her and her sister tightly and told them I hoped they liked the book. Despite how important the issue of diversity and inclusivity is to me, I find it very hard to talk about. I don’t post about it much, concerned about coming across as a “theater ally,” someone who acts a certain way only in the interest of having it reflect positively back on them. I think Twitter is partly to blame. For every sound opinion, there seems to be an equally sound conflicting one. Some people think white people should use our privilege to be vocal, some think we should be silent to let marginalized voices be heard. Some say we should identify ourselves as allies, some say we should cut it out with labeling ourselves allies in the interest of avoiding the aforementioned theatrics.

I struggle with whether I have the right to write a Cherokee-inspired character in Mae, or a black character in Rou, or a Latina character in Gemma. I struggle with how to write an epic fantasy set in an American world without appropriating culture. I struggle with wanting to tell everyone about my diverse cast of characters, wanting to insert myself in the “we need diverse books!” hashtags. I worry about unconsciously stereotyping. And I know I have little right to complain about the complexities of writing these characters, when at least I have the privilege of my voice being heard, rather than silenced, misconstrued, or told to change. So I tend to err on the side of silence, hoping that instead my work will just speak for itself. And tonight, it did. Two little girls saw themselves represented in the hero of a fantasy-adventure novel, just like I saw myself in Daine, and Matilda, and Saaski. Even this post feels slightly theatrical and disingenuous. But my gratefulness to those girls and their mother is real, and not because it makes me look good, but because this is the ultimate goal I've been working towards all this time--using my work to nudge inclusivity just a bit further. I wanted to tell them to wait until book two—that the romantic interest, and perhaps my favorite character I’ve written so far, is a young black man. But I didn’t. I just hugged them and thanked them for buying my book. I thanked their mother, and I told her this was important to me. I hope they like it.

5 Comments

Friends, I think the only way we make progress is when we stop saying "you, you, you" and start saying "I, I, I."

I am racist. I have made assumptions and had disrespectful thoughts based solely on someone's race. I have wrapped myself in my privilege and kept silent. And so... I promise to listen. I promise to take it upon myself to learn, and not force someone to teach me. I promise to believe that someone's pain is real even though it is not my lived experience. I promise to stop and examine myself when I make assumptions and look for justification. I promise to be more inclusive in my home life, in my work, in my parenting, in my writing, and in my art. I promise to work to undo the ramifications of my silence and privilege. It’s that time of year again. Summer. Travel season. When vacations planned years in advance finally come together. The kids are out of school. It’s time for families to take some time and just be together. It’s time to create memories everybody can share further down the line.

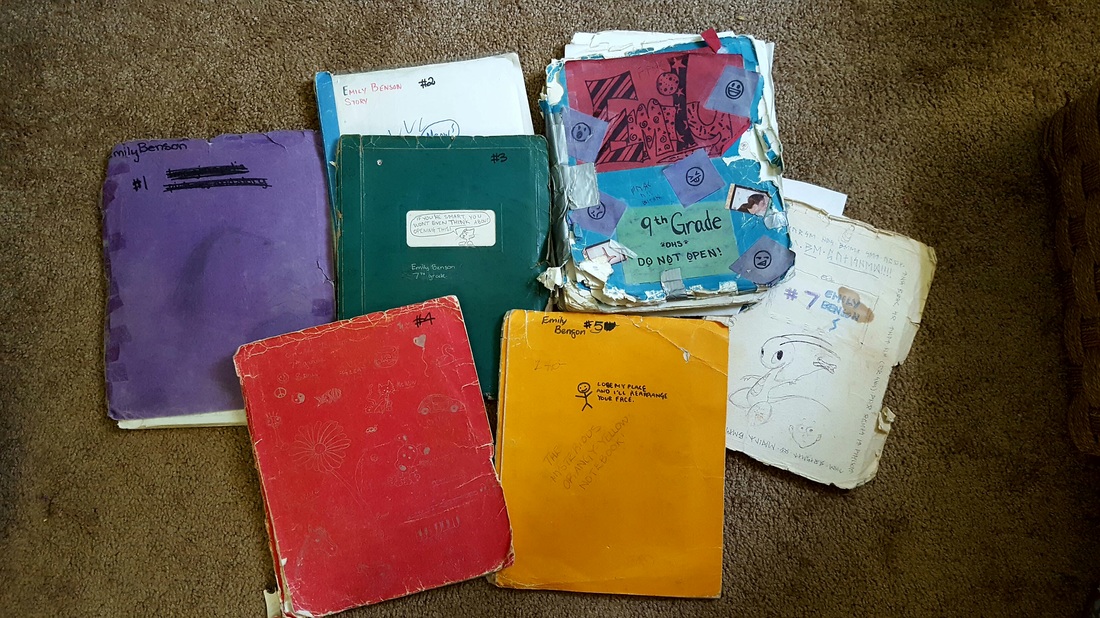

For me, though, summer is starting to mean the opposite. Summer is when I pack my suitcase, get my ranger uniform out of storage, and leave my family behind. My life as a stay-at-home mom transitions abruptly—not just into being a working parent, but being a working parent far away from my husband and daughters. It’s not as extreme as it sounds. Last summer, I spent a month on my own in Yellowstone before my husband and kids came out to spend the summer with me. They aren’t able to stay with me this summer, but being in Great Smoky Mountains means I am only two hours from home. They are visiting right now—the kids are napping on the couch cushions spread on the floor of the living room, since I only have one bedroom. So it’s not so bad. Some people face much more intense separations from their family for much longer lengths of time. But that doesn’t make saying goodbye any easier, and it certainly doesn’t alleviate the significant level of guilt I feel as I drive away from my husband—left alone to be a single parent, and my kids—without their mom for a chunk of the summer. I have gotten pretty good at driving while crying. I usually end up holding lengthy conversations with myself to talk through this decision to put my two degrees in park management and visitor services to use. They often start with the same questions. Why am I doing this? Is it really worth it? I have my degrees my whole life—my kids are only young once. Is it unfair to them? Will they be sad? Will they miss me? What if they don’t miss me? Will they behave for their daddy? Is it unfair to him? At least when I stay home during the school year, he comes home at night. He says it’s okay, that he likes having the chance to spend more time with the girls than he does during the rest of the year, but is this going overboard? Those other moms at church—the ones who homeschool their children and teach Sunday School and host juice and cookie parties—they wouldn’t do this to their families. Their families are more important to them than a career. And that’s right, isn’t it? That’s how it should be for a mother. At the most recent goodbye, when I pulled out of the driveway for the Smokies, this narrative got me through civilization and into the national forests at the state line. The sprawl of urban South Carolina gave way to the Chattooga River and the evening light of the Georgia mountains. The land began to rise and fold. I wound up, up the steep road through Flowers Gap while the Avett Brothers serenaded from my speakers, I just want my heart to be true, and I just want my life to be true, and I just want my words to be true—I want my soul to feel brand new. Shifted into low gear on the far side and careened down, down, flanked on all sides by the emerald swells of the Appalachian foothills. Turned north to Cherokee. It’s no secret that this landscape is magic to me. I wrote an entire novel romanticizing the mountains and the culture and the flora and fauna. Heck, I sanctified our native fireflies. And here in the Smokies, we’re in the thick of firefly season! I get to give a ranger talk to people who have traveled from far and wide to see them! The synchronous fireflies, the evening and flashbulb fireflies, the blue ghosts—my favorite—I get to be the cover band for folks riding the trolleys to see them. The Catawba rhododendrons are blooming at high elevation—bursts of ostentatious purple-pink amid all the green. Women’s Work festival is coming in a few weeks—women will stream into the farm to show visitors how to spin yarn, cook on a hearth, and forage the forest for medicinal herbs. My programs on mountain farm life, birdsong, and stream creatures have to be researched. I’m surrounded by ranger hats! Surrounded by the background chatter of the park radio, the rooster screeching down on the farm. Kids bringing me their Junior Ranger books, ready to show me their work and be officially sworn in and given their badge. My family got to be here for my first day back in uniform. As I got ready to head out the door, Amelia put a Frisbee on her head and said she was a park ranger. Lucy has already learned to identify mountain laurel and veeries, just as quickly as she learned aspen trees and ravens last summer. They leave tomorrow, and I’ll spend my days in uniform and my nights writing and drawing (except when I’m with the fireflies). During the week, I’ll Skype with them and hear about how they got to go to the hardware store and how Dad had a surprise for them and it was pudding! And then on my next set of lieu days, I’ll drive back down to see them. And do it over again. The goodbyes might get easier throughout the summer—but I doubt it. Despite this, I am happy with what my family has chosen to do with our summers. I was happy about it last year, and I’m happy about it this year. There are sacrifices to any lifestyle. Because I have a family, because I have kids who will be in school and a husband with a solid job, I know I will not be pursuing a full-time ranger position, not for a long time, if ever. I will be working seasonally long after my colleagues have landed permanent jobs or moved on to a more stable field. But I’m happy with that, too. And I’m happy to think about where we might go in the future—what new places and exciting adventures might become just another part of my kids’ childhoods. Last year it was seeing Old Faithful erupt every day. This year it’s probing deep into the rich forests of southern Appalachia. That, to me, is worth it—even if we have to say goodbye for a little while to make it happen. It’s Ms. Amberg’s seventh grade math class. People are packing up for the lunch bell. Near the door, a group of students huddles around something, sniggering. I have a bad feeling in my stomach. “Hey Emily,” says one. He waves a scrap of paper. “Emily, Jacob Brent wants you. He wants you so bad.” This was at the very turn of the millennium, when the internet was just moving from being a weird, mythical beast to an everyday commodity. Fan websites were sparse and ill-organized, and search engines were clunky and slow. So it was a significant occurrence to find rehearsal photos of one of my favorite Broadway actors online. Significant enough to write an exuberant note—probably with a lot of capital letters and literal squees—to my best friend, who shared my obsession with musical theater. A note that had been read by my friend, acknowledged with mutual amounts of enthusiasm, crumpled, and thrown in the trash, where it belonged. She knew something like that couldn’t just be left lying around. But it didn’t stay there. For whatever reason, the note had been subsequently pulled out of the trash and read by this group of popular, cliquish friends. “Hey Emily,” says the ringleader. “Jacob Brent thinks you’re so hot.” I remember exactly who that student was, his name, his face. And I’m sure in the years since seventh grade, he’s matured into a kind and generous adult. But it doesn’t matter—I will always remember him this way, laughing at my nerdy note—my private note—where I had shared a little bit of my delicate tween heart with the only other person who would cherish the information. I’d venture to say middle school isn’t easy for anyone. Everything is uncomfortable and everything is important. During those years and beyond, I was painfully embarrassed by my undeniably geeky interests and hobbies. Musical theater was only the first strike. Epic fantasies were strike two (this was before the Lord of the Rings movies came out and hobbits became suddenly desirable). My own novels handwritten in spiral-bounds were strike three. And, to make matters worse, I documented the ebb and flow of all my obsessions in my sketchbooks. I think I would have stopped drawing and writing, if I could have. In fact, in many cases I would sit, picturing a sketch in my head but resisting the urge to put it on paper, because it was simply too geeky, and I didn’t want it physically existing in the real world lest it fall into the wrong hands for someone to judge me. But art was my main creative outlet, and I couldn’t stop everything. To compensate, I drew hunched over my page with my free hand blocking my pencil. I guarded my sketchbook carefully and shared it with only a few people. My writing I kept even closer. These were pieces of my heart, laid down in dangerously concrete form—God forbid the wrong people (which was nearly everyone) see them. It shouldn’t have mattered. Everyone knew I drew, everyone knew I wrote, everyone knew I was into sword-and-sorcery novels. Everyone knew I was a nerd. It shouldn’t have mattered. But it did.

I don’t share this because I want a pity party or to bemoan the fact that kids can be dicks to each other. I share it because I want to illustrate my baseline—the underlying current for much of my life. I was the opposite of a proud geek. I did not let my geek flag fly. I was so, so embarrassed by the literature, movies, and pastimes that interested me. Art and writing mean being vulnerable—you’re airing out the inner workings of your head and heart, which are usually best left locked up. And that was nearly unbearable to me, from middle school all the way to around, oh, 2014. My husband didn’t even know I wrote recreationally until nearly four years into our marriage. It was the only secret I ever kept from him (except for the chai lattes I occasionally buy after exceptionally grueling grocery store runs). And that’s why I’m sharing this blog post now, the week of my first novel’s release. Because know what? I don’t feel this way about Woodwalker at all. If you follow my Facebook page, you see all the sketches and finished pieces I post. Facebook! Not DeviantArt, where I can lose myself in a community of other geeky artists and hide behind a username. Not Twitter, where I’m insignificant enough to just be part of the background noise. Facebook—a place where you can see my face in my profile picture, where my actual, legal name accompanies the images and excerpts I post. Where I am personal acquaintances with at least 50% of my followers. And I don’t care at all! And I know when I started not caring. It was when my husband found out about my writing, shortly after my second daughter’s birth. In our old house, our WiFi was pretty patchy and would often cut out during bad weather. One stormy night, after the kids were asleep, I was working on a different novel, always careful to keep my screen tilted away from my husband, who was doing some work of his own. I was getting pretty excited about my impending plot twist, and I’m sure my typing was louder than the rain outside. After a little while, my husband looked up and said, “What are you working on?” My answer was automatic. “Oh, you know, just Facebook and stuff.” (Because that’s so much more worthwhile than fiction writing.) He paused. “Do you have Internet? My Internet’s been out for an hour.” Well, I was caught. I’m not that good of a liar, and even if I was, my brain was too wrapped up in my thickening plot to come up with anything. He saw the slightly panicked, deer-in-the-headlights look on my face and got suspicious. “What are you working on?” “Nothing.” “You’re typing like crazy, and our Internet’s out. What are you doing?” “I’m… writing.” “Writing what?” “A story.” “A story?” I’ve found there are generally two kinds of people—those who find writing enjoyable, and those who find it to be a unique form of torture. My husband, a civil engineer, is decidedly the latter. So his consternation was mostly born from the revelation that I was willingly subjecting myself to such drudgery. “It’s a fantasy story,” I said, with that same sudden flight instinct I felt in my seventh-grade math class. “Like… sort of like a book.” “How long have you been working on it?” “I dunno, a while.” Months. He could have responded in any number of ways. At the time, we were a four-person family just getting by on his single income, so he was understandably money-conscious. He could have asked why I had been wasting so much time when I could have been contributing to our finances. He could have gone back to his own work and ignored me. He could have laughed, or blown it off. It’s a mark of how sensitive I was about my art and writing that I half-expected these things from him—not some cocky tween athlete, but my husband, the guy I picked out and said, “yeah, I’ll hang out with you for the rest of my life.” That’s how delusional twenty-six years of self-fabricated shame had made me. Because of course he didn’t do any of those things. He said, “What’s it about?” And then neither of us needed WiFi for the next four hours, because we talked the rest of the night. We talked about my current story, my characters, my plot, my setting. We talked about my past stories—the things I had written in middle and high school and only shared with my best friend, the things I had written in college and shared with no one. We talked about my future stories, including this little germ of an idea in the back of my brain—the one about a forest ranger on a quest to restore a fallen country. And then he asked the obvious question—“Are you ever going to try to publish something?” “Oh no,” I said quickly. “No, I have no idea how any of that works, and I couldn’t publish this anyway.” “Well,” he said. “It might be neat to try.” Apparently that was all I needed, that little bit of affirmation. I started writing Woodwalker later that week. A little over a year later, I signed a contract with my literary agent. And now, a year after that, I am approaching the publication date for my debut novel. Yes, this means I needed outside validation to legitimize myself and my passions. I admit it. And I don’t care about that, either. After my overblown childhood sensitivity, it honestly doesn’t surprise me at all. I wrote a novel! It’s being published! And you know what? I LOVE MY NOVEL. Not all of it, and not all the time, but I wrote it, and I love that I wrote it and that it’s mine. And it’s going out into the world! People are going to read it! Some people will hate it! Some people are going to leave disappointing reviews! Some people will even get nasty and mean-spirited! The book may tank and sell terribly and be pulled from shelves! And I don’t care! I’m so excited to have gotten to this point, to be sharing it and my art—my geeky, compulsive art that throws wide all the windows and doors to the quirky, convoluted parts of my brain—and not be feeling like I need to hide it or apologize for it or awkwardly laugh at what a geek I am. That feeling, even more so than publication, is Success for me. This post has clearly turned into something with some kind of moral, and I’m not sure what it is. I’m not going to tell you to believe in yourself, because God knows I didn’t despite being ordered to in every Disney movie and grade school pep rally ever. It could be surround yourself with supportive people, but even that doesn’t ring true, because I had supportive people around me my whole life and didn’t even trust them. In reality, the takeaway message is probably just grade school blows, especially that one guy in math class. But maybe I’ll just leave things blank and let readers create their own meaning. I’m just happy to have gotten here, proud of my work and excited about sharing it with people. I talked to a high school friend on the phone the other day, and she was congratulating me on my book. I told her how strange and surreal it still felt to be publishing something. “Nobody is surprised, Emily,” she said with a laugh. “Absolutely no one is surprised by this.” Maybe no one, then, except me. |

Emily B. MartinAuthor and Illustrator Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed